It was the of confluence streams; the scientific stream of the previous fifty years joining the commercial pest exterminating stream — those mercenaries who fought the termite wars over the same fifty years.

It was the first Tuesday in February 1956.

The scene was the colonial brick and slate-roofed building of the Sydney Technical College in Ultimo, inner Sydney. All the empty student desks were waiting in anticipation for 6:00pm. At the teacher’s desk, a 32 year old man in a grey suit, sat separating hand-out papers into piles of 30. About 5:30 ish the first students tentatively drifted in because they didn’t know the teacher, each other or what to expect.

They were about to experience this first, formalised educational merging of scientific knowledge and practical experience.

* * *

An Intermediate Certificate at Farrer Agricultural College in Wagga Wagga was just the first scholarly achievement for the lad; then it was off to the Big Smoke of Sydney and the Hurlstone Agricultural High School at Glenfield (where there was very little smoke) but high academic expectations for Leaving Certificate graduates.

Phillip Hadlington had no trouble exceeding those requirements and he entered the Faculty of Agriculture at Sydney University.

Every three months or so, the Uni students in Agriculture were sent out to work on properties around NSW. Apart from the invaluable practical experience learned from no-nonsense rural people with their livelihood and often their properties on the line, he consistently found farmers and graziers with a soft spot for the NSW Forestry Commission. By the time he was ready for graduation, Phil had decided entomology was his calling and particularly in the field of forest insects.

Going straight into the Division of Wood Technology in 1947, he was involved particularly in termites and borers, the insects that were anathema to buyers of timber which the commission was growing. Soon a sideways shuffle saw him in a new role: Forest Entomologist. His new job, which lasted for 36 years, was to developed ways to minimise insect attack and damage on the growing trees and the felled logs while they were still on Forestry land. From the leaf-devouring giant stick insects or Phasmids, to the little sap-sucking lerps that the bellbirds fed on while chiming delightfully in gullies of tall eucalypts, Phil learned what they did and whether and how Forestry resources and money should be allocated to their control.

This role often took him to Melbourne, Brisbane and Canberra to talk to forestry counterparts. This fraternity of entomologists led Phil to interaction with the top brass at the CSIRO. He didn’t, but he could have name-dropped “Waterhouse, Ratcliffe, Gay, Greaves and Hills.” DF Waterhouse was the Chief at CSIRO and the others were top researchers and authors specialising in termites. He particularly got along well with Norm Tamblin at CSIRO and Frank Gay, who was originally a first class botanist before he became a first class Termiteer. Frank’s botanical background and tree identification knowledge was of invaluable help to Phil — and he’d done more termite research than anyone else Phil had found.

* * *

The first commercially inflicted defeats on termites came with Bill Flick’s arsenic dusting techniques. Dusting was then the overwhelmingly preferred option until the advent of the long term residual organochlorines which had almost taken over within the decade after the war.

This post war decade, like the four decades before WWII, was a time when information was difficult to find and even harder to evaluate because so much misinformation swirled like fog around the truth. If it could be made to sound plausible, it became gospel. Buyers of pest control services too often became victims. The peddlers of pest extermination knew just a bit more than a homeowner, a factory manager or a brothel madam.

Being based in the CBD of Sydney, it wasn’t long before Phil Hadlington was being approached by pest control companies for advice and help in identification and advice on termites and borers. In the 1950s, his office was two storeys up steep sandstone steps in a turret of the Presbyterian church in Margaret St. No wonder pesties over the years thought he was an all-knowing god.

Keith Brooke was Technical Director at Flick & Co, George Clarke was his No 2 and they spent a lot of time sucking entomological information from Phil that ended up in the constantly evolving Flick Training Manual. Plenty of one- and two-man pest control company principals also found their way to this other god in the city church. Locals including Andy Ramage, Ted Ellis, Arnold Farrell, Arthur Atkinson and, from Newcastle, Thomas Cowan and his son Bob sought audience to discuss treatment options and problems. The second biggest Australian pest control company, Houghton & Byrne, was just down the hill in George Street and Service Managers Doug Tristram and Garth Mitchell were regular visitors. Questions were often asked about pests other than termites and borers so Phil quickly got up to speed on all the pests that bothered people and industries.

Many government departments were receiving an increasing number of disquieting enquiries and complaints about pest service companies. The Forestry Commission of NSW had been constantly fielding calls from victims of termite attack and inept control efforts. The NSW Health Department were hearing from their Health officers and council Health Inspectors told stories of uncontrolled rodents and cockroaches, bedbugs, fleas and ants.

A noxious cocktail was being served to the citizens: pesticides that could kill quickly or slowly in the hands of untrained and unregulated operators who saw an opportunity to work for themselves. Several hundred stories could be written on the misadventures of this era. Let’s hope they aren’t.

The Department of Technical Education was given the task of developing a course and finding someone to teach it.

The pest control service companies were far from organised; there was no one to speak for them as a group, however when various companies were asked if they would support a course by sending employees to learn skills and knowledge to assist them in their work, they promised they would.

There was a need. And there was a man who filled it.

This February night, the young Forestry Commission scientist at the front desk was set to bring knowledge to the needy. His job? To educate. To provide answers to questions the industry didn’t even know to ask; to build into the students’ thinking, a structure of protocols and thought processes to evaluate pest problem situations based on the recognition and identification of the pest, its life cycle, its known and instinctive habits in its habitat, the range of possible treatment options, the insecticidal consequences for themselves and their customers and the Acts and Regulations under which they operated their businesses. No pressure.

The students were mostly the bread and butter operators of large and smaller companies and the sole owner/operators who had left their previous employer to make money for themselves instead of the boss. Many ran a single-man operation with their wife, the unpaid receptionist-appointment-maker-bookkeeper and doer of every other task not involved in inspecting, quoting or spraying. Up until this course started, bosses had not told staff any more than they wanted them to know. Their reasoning was simple: if operators knew too much, they might go out on their own.

Houghton and Byrne provided students, mostly supervisors and leading hands who might bring better skills and knowledge into the H&B team. Powell’s Pest Control and Acme Pest Control provided a couple each. Government employees from the Maritime Services Board and the NSW Public Works Department took up some desk spaces. (Flick & Company boycotted the course for its first three years for exactly the reason stated earlier; they had by far the best training system and didn’t want their team learning more about pesticides that could make it easier for their operators to become opposition companies).

What students hadn’t been taught by their bosses was due, in part, to the fact their bosses didn’t know the biological facts of life either. Which really meant the providers of paid-for pest control services were relying far too often on witches brews, subjective evaluation of what they perceived had worked, and very much on what seemed a plausible story a customer might believe before handing over money. A ready smile and “good bloke” demeanour would hopefully clinch the deal… if the price was thought reasonable for the promises made.

* * *

For the impending course, Phil Hadlington had to learn about all the other pests — including pests of homes and commercial enterprises, even teredo and other marine borers — and meaningfully teach identification, biology, habits and control options for all of them.

Most of the thirty starters of the first course finished it. Which in itself says plenty about Phil’s style, patience and teaching ability. Many of these men struggled to become students again some 15-20 years after they’d left school, having hardly written more than their name and maybe never having drawn anything in the intervening time. Now they had to take notes because the handout papers were short on detail; they had to struggle with a new language: latin for names like Coptotermes acinaciformis, and there were names for body parts of insects: malpighian tubules, enteric caecae, spermatheca, etc. Most of them loved it.

During one of the earliest of the two-nights a week, one-year course, Phil gathered the students around the main desk and, with tiny stainless steel scissors, narrow scalpel, forceps and tiny, size 20 entomological pins to hold things in splayed out position, he dissected a phasmid while conversationally describing what he was cutting and pulling apart and revealing.

By the time the final exams were completed in late November, students had been exposed to insect anatomy, physiology, life cycles and habits, had learned to identify the main pests of homes and industry, had learned the various treatment options for those pests in various situations and circumstances, and wonder of wonders, the names of the pesticides and how to use them safely and effectively. They had to collect, display and hand in an insect collection containing specimens from a dozen different insect Orders which also included a number of identified and labelled pests. Their workbook containing the notes and drawings made during the year was also to be handed in.

The first course was adjudged by the Tech education people a success so it was repeated again and again, always improving. Phil was almost omnipotent. The students liked Phil and the way he involved them and that he expected they could do it. So they did. He ran that course for decades and as Ion Staunton recalls from his later, 25-year involvement in the Association, “I met hundreds of Phil’s ex-students. I never met even one who didn’t praise Phil and feel better about the industry they were in as a result of a year at Tech (or completing a correspondence course marked by Phil)”.

* * *

Many who knew Phil back then, saw his prickly side if the customer was not receiving value and efficacy, delivered safely.

Phil was regularly stirred up about injustices and incompetence. Not just homeowners ripped off by pest controllers but even car manufacturer Chrysler who could not build a car (the Centura) that didn’t drip oil on his garage floor. This subject was given many minutes at half-time during one evening lecture; it gave students a clear understanding that the people had definite rights to expect competency, justice, truth, value for money — everything we now consider to be consumer rights. The movement for consumer rights was just beginning. Ralph Nader had just written his seminal expose´ “Unsafe at any speed” relating to the USA car builders/designers. Phil expected his students to deliver the goods to their customers.

Then in 1963 a Phil Hadlington-engineered crisis hit the industry.

He asked the Dept of Wood Technology to inspect a home that had a termite attack and to recommend what action and treatment should be recommended. Then they had the homeowner call in various pest control companies to inspect, make their recommendations and give written quotes for comparison.

It was a debacle.

Some quoted extravagantly, some found things that weren’t there and some found nothing at all but quoted for barrier treatment and annual inspections. The prices were disparate.

Choice Magazine was fired up with the enthusiasm of its early years. When that termite exposè issue of Choice was published, all the Sydney daily newspapers gave it headlines. There was nowhere for pest controllers to hide.

Aged 40, Phil the change agent became the unifier, the facilitator,.

Flick had set themselves up as the only member of the National Pest Control Association; another group calling themselves the New South Wales Pest Control Association were little more than a buying group seeking discount prices from Shell, Velsicol, Bayer and Ciba-Geigy.

Members of both Associations separately sought solace in Phil’s chapel. Instead, they were counselled to get their acts together. He explained this was an opportunity for pest controllers to change from being perceived as charlatans, con men and untrustworthy to be what they could become: ethical contractors with knowledge and skills to deliver homeowners from the financial and health risks of pests. They could provide value for money, delivered safely.

A meeting was called to be held at Science House in Gloucester Street. Phil was the convener, phoning and encouraging attendance. He asked Ion Staunton to be the minute taker.

It was a very subdued meeting; the expected excuses, the anticipated blame game and finally the hoped-for “let’s get ourselves together.” It was decided to form a combined association and a month later, on the 23rd August 1963, the meeting resulted in the United Pest Control Association (of NSW).

Choice Magazine may have been the catalyst but Phil Hadlington was the reason the Sydney pest controllers began the process of becoming an industry.

The role of Associations and their development changed from an emphasis for doing the best for the members to the objective of doing the best for the customers with reliable management of pests, safely delivered— which of course was also good for the members that could deliver what customers wanted.

That was the heady era of change and effort. Phil kept teaching —and developing people for significant roles.

* * *

He asked people at any level to help —and they willingly did. He bought in Geoff Simpson from NSW Occupational Health to take the sessions on that subject.

To some, he seemed aloof and demanding of ethics. It seemed he thought there were no shades of grey. He had become the major influencer. He was the major change agent.

Ion Staunton was a 1959 student. At the Presentation Night when all the Ultimo courses assembled to get their certificates Phil asked Ion who had topped the course, to come to his church office next week for a chat. He was impressed by Ion’s hand-in book, particularly the drawings, and asked if he would illustrate the text book he was working on. Until then there were only occasional handout notes from many and varied sources and he wanted a text book specifically for the course. Ion started drawing right away. Pests of Australian Homes and industry was self-published in time for the course in 1961.

The Foreword from Doug Tristram, Service Manager of Houghton & Byrne says a few things about Phil and the times:

“There have been frequent occasions when the practical men of industry have sought opinions and advice from scientists only to be disappointed by a seemingly vague or negative response. This resulted in business men concluding that, while scientists are valuable for contributing material for discussion, it must be the practical men who implement the decisions that emerge.

“Those of us who have associated with Phil Hadlington know him as a positive and objective scientist who not only takes applied entomology seriously, but is enthusiastic about producing a solution for a problem of pest control. We regard him as one of us because he maintains a down-to-earth attitude to us and our needs and does not tend to seek the isolation and remoteness of the pinnacle-abiding academician.

“This book will be welcomed by those who, because of distance, time or commitments have not been able to become a student of the Pest Control Course at the Sydney Technical College, of which Mr Hadlington has been the lecturer in charge for many years”

The first edition was typed onto waxed Roneo sheets, the drawings onto waxed sheets so that the typeface and lines of the drawings removed the wax film to let the ink go through to the paper. It was cheap and cheerful — and sold out quickly. New South Wales University Press Limited produced the second edition in 1962.

Staunton was given some subjects to teach at the course; Phil didn’t need to be teaching every subject if others could do it under his guidance. They began writing the Pest Control Correspondence Course.

John Gerozisis was a TAFE teacher who eventually took over from Phil, and with Staunton busy on Association and his own Pesticide Company business, John completely re-jigged and re-wrote the text book, Louise Beck did new drawings in what became Urban Pest Control in Australia in 1985. Just as the word “exterminator” disappeared “pest control” was polished to become “pest management” by the Australian Environmental Pest Management Association, so it became Urban Pest Management in Australia and went through a series of revisions before Ion Staunton was again given the job for a major revision and update as the fifth edition under the same title in 2008.

* * *

Phil Hadlington liked books. He really liked writing books.

In 1980 he worked with Joe Dark a Forestry Commission photographer to produce a mostly black and white book: Trees & Shrubs for Eastern Australia. Then he saw the need for a book on spiders so again Ion Staunton was co-opted to do some drawings this time in ink. Phil developed close up photography never before seen. The venom dripping from the fangs of a funnel web spider is still the iconic spider photo of all time. He pulled his Nikon apart, attached bellows and whatever else was needed to get up close and very personal yet still be far enough off the subject so that light was not blocked out. He even developed a circular light to surround the lens. Things now taken for granted on any smartphone. The 46-page booklet was published in 1962 as Know your Australian Spiders and Ticks but the designated author was given as B Hadlington, Phil’s wife (for reasons best known by the NSW Public Service Board and maybe for taxation purposes).

Disaster. Betty, Phil’s lovely wife and mother of Julie died of cancer… aged just 34. The church in Hurstville couldn’t hold all the family and the industry people who turned up in respect.

Some years later, Phil remarried, to Val, who just so happened to be a member of Manly Golf Club which had many trees along the fairways in various states of disrepair and life threatening circumstances. Phil decided he could do three things: help the trees, help the Manly Golf Club and use the venue as an opportunity to run a tree surgery course for pest controllers who were unafraid of heights and who could see a profitable sideline to mainstream pest control. And, maybe he had thought ahead to another book.

With Staunton again as his offsider, they began a Sunday morning tree surgery course. From way up in the branches of a gum tree tattooed with golf ball marks, Ion remembers looking down at HC (Nugget) Coombs, whose signature was once on all our banknotes as Governor of the Reserve Bank, as he left his buggy and ambled over to ask: “G’day Phil, what’s happening here?”.

With book production imbedded in their psyche, Hadlington and Staunton decided a book on tree surgery would be a good idea but, as that was a very restricted market, they decided to include the minimal tree surgery and care stuff inside major sections, front and back, on Trees for Colour and Trees for Shade. The book Trees for Australian Gardens didn’t make the best sellers list but from the first edition in 1971 it sold very well and went through three editions and a couple of reprints.

The text book that has a place in the glove boxes or cases of most pest managers is Australian Termites Hadlington and Staunton. Just 140 pages, it is well illustrated by Louise Beck and has concise details of the major termites found around Australia with helpful maps showing distribution of each genus/species. It was first published in 1987 and revised in 2008

A small book called Household Pest Control… Eradicate the pests in and around your house without endangering the environment.

Phillip W Hadlington and Noel Cooney It was published in 1973.

Next came a couple of books specifically for homeowners: Common Household Pests, a homeowner’s guide to detection and control and followed in 1998 by Termites & Borers, a homeowner’s guide to detection and control both with Christine Marsden, the daughter of Noel Cooney. Val and Noel Cooney were first cousins and only-children who grew up together in Manly. Phil became part of that family when he married Val.

* * *

He “retired” from the forestry Commission but kept active, working with Ted Taylor in a small consulting entity and, in 1995, Doug Howick of CSIRO and Victorian Association and later Executive Director of AEPMA fame, asked him to write a course on termites and another on wood technology. He still marked correspondence course papers. Pesties dropped by for a chat, a cuppa and advice. That was his early version of “retirement.”

There was a fight he did not win. However, he has the right to say “I told you so!” In the late 60s, home builders made the wholesale change to slab-on-ground concrete floors, away from traditional suspended wooden flooring. Phil said it was going to cause more termite problems and, that by the time termites could be discovered, the damage would be extensive and expensive. He had organised a survey in 1970 which showed that 3% of homes had a history of termite attack. In 1983 a follow-up survey reported 20% of buildings had a termite history. In 2006 it was running at 33%. He was right.

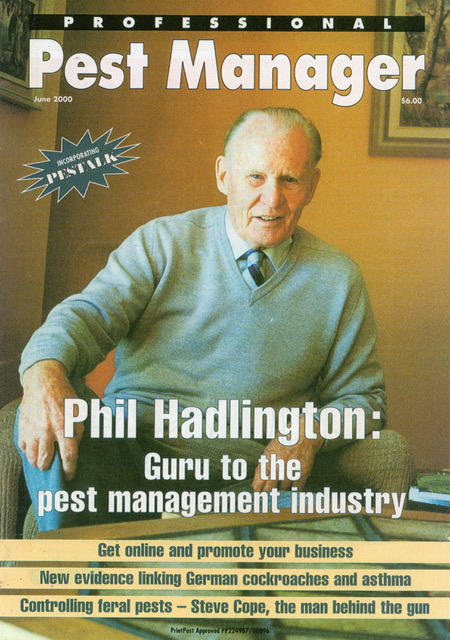

When Eric Cope was president, the Association organised the Hadlington Appreciation Evening. Phil and Val were picked up in a vintage car and driven to the event to hear speakers proclaim the value of the man that almost single-handedly changed the industry for the better. In 2000, he was awarded the Order of Australia Medal. Phil Hadlington OAM.

He “retired” from the forestry Commission but kept active, working with Ted Taylor in a small consulting entity and, in 1995, Doug Howick of CSIRO, Victorian Association and later Executive Director of AEPMA fame, asked him to write a course on termites and another on wood technology.

He still marked correspondence course papers. Pesties dropped by for a chat, a cuppa and advice. That was his early version of “retirement.”

He dropped everything that had defined him in pest management and entomology to nurse Val through her last couple of years. After 40-something years together, he loved and treasured those memories.

As too often happens, when Val died, the phone calls trickled to not many. Ion rallied a couple of stalwarts to keep Phil in touch; they may or may not have been his life preservers but they didn’t stop him being lonely. From full time carer, housekeeper, cook and bottle-washer he suddenly had no one. Not true. He had his neighbours, particularly Dr David and Barbara Goodall. They invited him over, they dropped in, they cared. They let him walk their dog so he could continue to meet people. He didn’t try to pick up the past that made him a big name in our circles.

Finally, he went into Estia Aged Care at Manly Vale. He loved the Bingo sessions but over the last few years dementia hid his mind in bubble wrap. Amazingly, on Australia day 2021 his daughter Julie visited and the fogs blew away; he even named his grandchildren correctly and had a great time.

He used to joke about the publication details page inside the front cover of his books which has all the details no one reads: publisher, date, National library number and, besides the authors’ names, the year they were born and a long dash.

For Phillip Walter Hadlington it was: 1923 —

“You can see you are not immortal” he used to say, “when you see that dash beside your name; they are waiting for you to die!”

It finally came to pass at aged 97, on Monday 29th March 2021.

Most people reading this never knew him; a few may have noticed his name on the cover of the main industry text books. Many of those that do recall those dim and distant times have retired from active service, and so, Ion Staunton, while still having some marbles, took it upon himself to let the current movers and shakers know that there was a man who moved and shook like no other in our industry.

Phil never set out to be well known and respected; he became that way (and more) because of the things he did and said… and by developing people at many levels to make the changes that have happened continually. Incremental changes made by those influenced by Phil who have influenced others over the last 60 plus years… continually building a better industry. Agree?

Thank you, Phil Hadlington OAM.